This posting is also accessible HERE.

In recent weeks, Rafizi Ramli has stepped up his criticism of Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s administration — this time sounding alarms over alleged erosion in judicial independence.

At first glance, his concerns evoke Malaysia’s long history of state interference in legal institutions. But on closer inspection, his arguments raise an uncomfortable question: Is this a principled stand for justice, or a political rebrand in the run-up to GE16?

Malaysia's Judicial Wounds Run Deep

Let’s start with what Rafizi gets right.

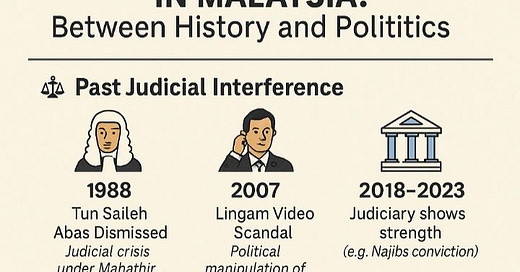

Malaysia has a painful legacy of executive overreach into judicial affairs. In 1988, then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad orchestrated the dismissal of Lord President Salleh Abas — a move widely condemned by legal scholars and human rights advocates¹.

Two decades later, the Lingam tape scandal exposed backchannel negotiations to influence judicial appointments, again under Mahathir’s watch². These episodes left lasting scars, shaping public distrust in the system and affirming why vigilance is necessary.

What’s Happening Now? Is There Interference?

Fast forward to today, Rafizi suggests that Anwar’s administration may be meddling with the judiciary. But where’s the evidence?

In reality:

Najib Razak’s conviction and imprisonment for the 1MDB scandal was achieved through a robust legal process — not executive manipulation³.

The controversial DNAA (discharge not amounting to acquittal) granted to Zahid Hamidi was a prosecutorial decision, not a judicial one⁴. Legal scholars and even the Malaysian Bar criticized the move, but they did not frame it as judicial capture.

Without whistleblower testimony or leaked communications (like in the Lingam case), Rafizi’s claim remains speculative.

The Real Game? Positioning for GE16

So why the sudden judicial crusade?

This may be less about principle and more about political recalibration.

Rafizi, having exited the Cabinet, now wears the hat of a dissident-reformer again. He may be angling to rebrand himself as the conscience of the coalition — someone who "speaks truth to power" in anticipation of electoral realignments⁵.

This is a classic Malaysian tactic: Attack your own coalition when the winds shift, and the public starts murmuring about unfulfilled reforms. Rafizi is reading the room, and he knows discontent is growing⁶.

A Curious Alignment with Western Talking Points?

Here’s where things get geopolitically interesting.

Rafizi’s rhetoric — about institutional decay, rule of law breakdown, and democratic erosion — echoes liberal democracy discourse promoted by international NGOs and Western think tanks⁷. These groups often rank Malaysia as a "hybrid regime" needing reform, especially when it pursues non-aligned or Islamic geopolitical positions⁸.

Meanwhile, PM Anwar has taken firm stances on Gaza, leaned closer to BRICS+, and questioned Western moral authority. Rafizi, whether deliberately or not, may be aligning with external actors uncomfortable with Malaysia’s current diplomatic posture.

That doesn’t make him a foreign agent. But it does raise the question: Whose reform are we actually talking about?

What Real Reform Would Look Like

If Rafizi truly believes judicial independence is threatened, let’s hear policy, not just posturing.

Here’s what he should be proposing:

Transparent and independent judicial appointment processes⁹

Oversight board over the Attorney General's Chambers (AGC)¹⁰

Legal protections for whistleblowers in the judiciary

These are systemic solutions — not campaign soundbites.

Conclusion

Rafizi is right that Malaysia must never become complacent about judicial independence. Our past proves how fragile it is. But unless he offers solid evidence or constructive proposals, his campaign will look like a political maneuver, not a principled intervention.

We don’t need another hero. We need institutional thinkers.

FOOTNOTES

1. Harding, A. (1990). The 1988 Constitutional Crisis in Malaysia. International and Comparative Law Quarterly, 39(1), pp. 57–81.

2. Royal Commission of Inquiry on the VK Lingam Video (2008), Malaysian Bar Councill.

3. The Edge Markets, Chronology of Najib’s SRC Trial and Conviction, 2022.

4. Malaysiakini, Zahid Hamidi: DNAA Decision Under Scrutiny, 2023.

5. Khoo Boo Teik (2005). Beyond Mahathir: Malaysian Politics and Its Discontents.

6. Rafizi Ramli’s public commentary archived in KiniTV, Bersih forums, and The Malaysian Insider.

7. Freedom House, Freedom in the World: Malaysia Country Report, 2024.

8. Gale, F. & Morshidi, S. (2005). Globalization, Geopolitics and Higher Education Policy in Malaysia. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(16).

9. IDEAS Malaysia, Judicial Appointments Reform Brief, 2023.

10. REFSA, Oversight of the Attorney General’s Chambers and Institutional Reform, 2022.