1 TRILEMMA

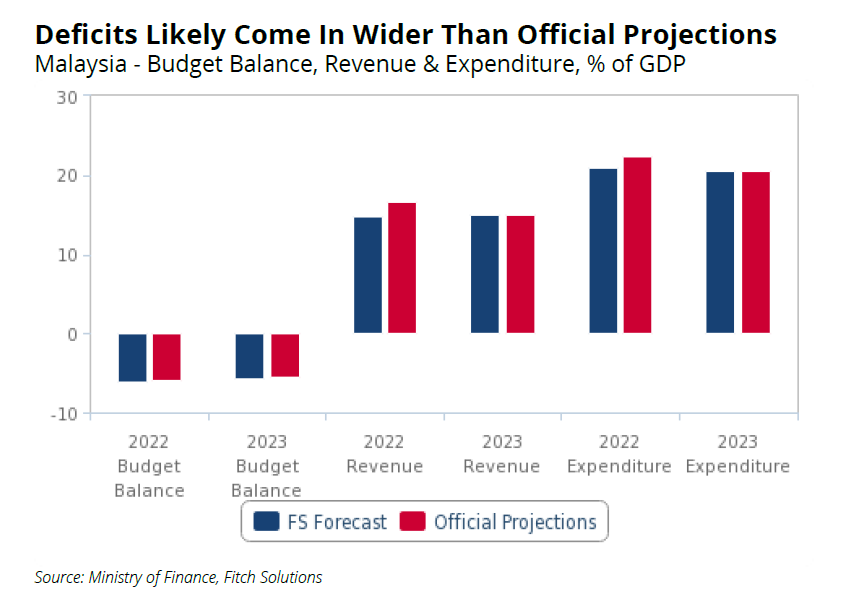

Economic affairs minister Rafizi Ramli said the ministry is set to face three big challenges in 2023:

how to ensure the government’s income can be optimised;

second challenge would be increasing the country’s revenue;

the third challenge involves the restructuring of the economy.

Indeed, it is the third parameter that is of utmost importance otherwise, the country shall forever on a subservient to a subsidy struggle between continuous demands for goodies without generation of revenue whereby expenditures are often spent on non-developmental projects that performed - and produced - the same thing over and over again with unpleasant and undeserving resultant outcomes that impoverished the poors but immensely benefitted the wealthy rich.

2 CHALLENGES

To ensure the government’s accrued income can be optimised on service deliverance to the rakyat with long-term socio-economic effect from “development projects”, it is duly acknowledged that competencies in the public service would have a larger learning curve impact on governance, and the sumptuous spread effect for the people.

The historical development of this nation has rested upon the effusing effort of extraordinary men and women who toiled in sawah, exploited in colonial estates and mines as indentured labour to the present spirits of entrepreneurs who shouldered the burdens of the small enterprising businesses that support

generating 38.2% of GDP and providing employment for 7.3 million people.

3 DEVELOPMENT

Towards any economic development in sharing common prosperity there needs to be in place developmental institutions and their productivity governance.

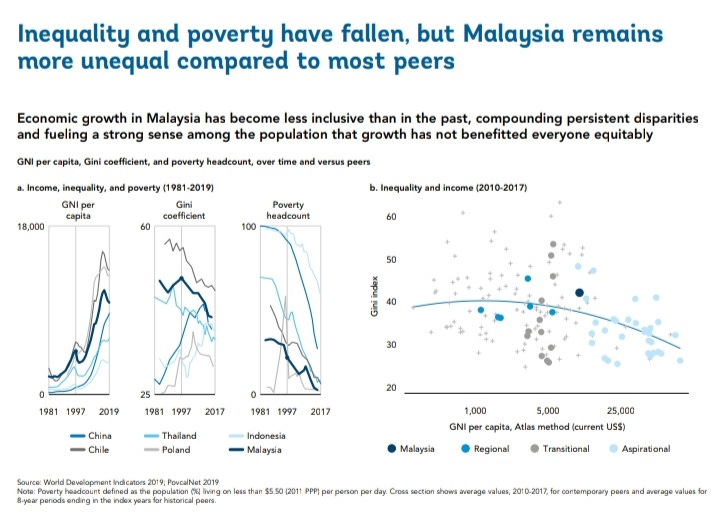

Reinert 2007; Reinert 2009; Vries 2013; Ohlin et al have collectively argued that structural change and innovative creativeness are the keys to escaping not only disparity in poverty, but a chance in sharing wealth.

What kind of development does a country need to share wealth within communities and between states? Second, what kind of institutions can promote development? Third, how to develop? These three questions are crucial to understand why Malaysia - despite 65 years of “developmental effort” - performance outcomes that are glaringly deteriorated among states, and between states; read A State underdeveloped.

Schumpeter made a fundamental distinction between economic development and economic growth. This distinction helps answer the first question. Mere quantitative growth does not amount to economic development: as Schumpeter (1934/2012: 64) argued figuratively that adding successively as many kerera api as one pleases, one shall never get a railway thereby. GDP growth nor Petronas towers, for example, do not equal Schumpeterian economic development. Economic development ‘comes from within the economic system and is not merely an adaptation to changes in external data; it occurs discontinuously, rather than smoothly; it brings qualitative changes or “revolutions,” which fundamentally displace old equilibria and create radically new conditions’ (Elliott 2012: xix). A country needs this kind of economic development to escape poverty (Reinert 2009).

From The quest for growth (World Bank, 2016) and steering the national economy (World Bank, 2019), by aiming high to achieve an accelerating growth path (World Bank, 2021), and to surge ahead (World Bank 2021b), the country is still, catastrophically, mired and entrapped within capitalism crisis to crisis in a struggle to catching up, (World Bank, 2022) among ASEAN peers:

Therefore, mere aiming high for accelerating growth with neoliberalism economic policies shall undermine, and underdevelop, Malaysia developmental effort under capitalism