created with and by DALL·E

Problems of CREATIVE DESTRUCTION in Malaysia economy

Malaysia’s prolonged struggle to transition from a middle-income to a high-income nation is rooted in extractive political-economic institutions that resist creative destruction.

Applying insights from the book Why Nations Fail (refering to authors Acemoglu and Robinson), one can argue that entrenched rentier elites and monopolistic structures stifle innovation, discourage entrepreneurship, and undermine inclusive economic development.

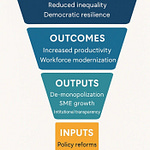

A decisive shift toward institutional reform and enabling creative destruction is imperative to rejuvenate Malaysia’s economic trajectory.

A brief Problem Statement on Malaysia’s economy is thus that the country is constrained by:

One, Concentrated ownership and control in state-linked monopolies (the GLCs);

Secondly, Protectionist policies that deter foreign and domestic competition;

The third point lies in the weak linkages between education systems and industrial needs;

Fourth dimension is the Patronage politics that perpetuate rentier capital over productive investment.

Overall, one shall say that these structural rigidities block the forces of creative destruction, preventing innovation-led growth and entrenching systemic inequality.

Specifically, in Malaysia’s context:

Entrenched elite interests —political and economic — have had resisted creative destruction because it threatens their monopolies, rents, and patronage networks.

These dimensions include:

Organisations like GLCs (Government-Linked Companies) dominating strategic sectors.

Then, we have protectionist policies favouring legacy industries and bumiputera capital.

Thirdly, we note the rentier behavior among politically connected conglomerates is concentrated, and often still encouraged.

Then, we further note that Policy Stagnation and Institutional Rigidity have choked innovation ecosystems.

For example:

STEM in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and TVET - the Technical and Vocational Education systems remain underdeveloped relative to South Korea or Taiwan.

There is a lack of R&D research and development commercialisation, despite government investments. Our nation's TFP - the total factor productivity - rating is a low-lying Asian tiger compared to Singapore, south Korea and Taiwan.

Further, there is much over-regulation of SMEs - in the small manufacturing enterprises, and even nowadays in emerging digital startups, thereby hindering creative innovation-led inventive solutions.

Add on political patronage and ethnic capitalism, these parametric realities have distorted the markets.

Many sectors (for examples in the, construction, energy, telecommunications sectors) are cartelised or semi-feudal, stifling competition.

In conclusion, one can express that without institutional reforms, Malaysia will remain stuck as a low-cost assembly hub whereon global investors will increasingly favour Vietnam or Indonesia which offer either larger markets or better governance reforms.

Then, the existing - and perpetuating - Class Inequality and Economic Dualism shall enable the cohorts of Rentier elites to continue accumulating wealth, while wages stagnate for the bottom 60% among the rakyat.

Indeed, youth, especially in urban areas, will face underemployment and precarity as the country is encased in a Middle-Income Trap Perpetuation

whence Malaysia risks becoming a “prematurely deindustrialized” country as such.