First published as and in

CAN ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE BRING ABOUT THE END OF A CENTURIES-LONG HISTORY OF INDUSTRIAL RELOCATION? THIS WILL BE A MAJOR TEST OF ITS CAPABILITIES

Di Dongsheng (翟东升)

Published by Guancha.cn on 28 April 2025

Translated by James Farquharson

Illustration by OpenAI’s DALL·E 3

The competition between China and the US over the global market for large [AI] models is essentially a contest for dominance over global political ideology." – Di Dongsheng (翟东升)

Thomas des Garets Geddes and James Farquharson

May 22 2025

Echoing our previous coverage of Professor Di Dongsheng’s analysis, this speech is characterised by a boosterish “China-first” style that stands out among some of the more pious rhetoric common in Chinese foreign policy publications. To a certain extent, it is refreshingly unusual to come across an international relations scholar in China producing statements such as “the battle for global industrial leadership is not a win-win scenario, but a zero-sum game.”

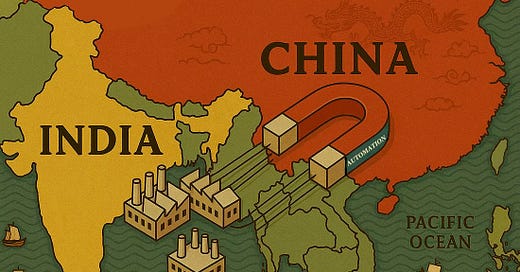

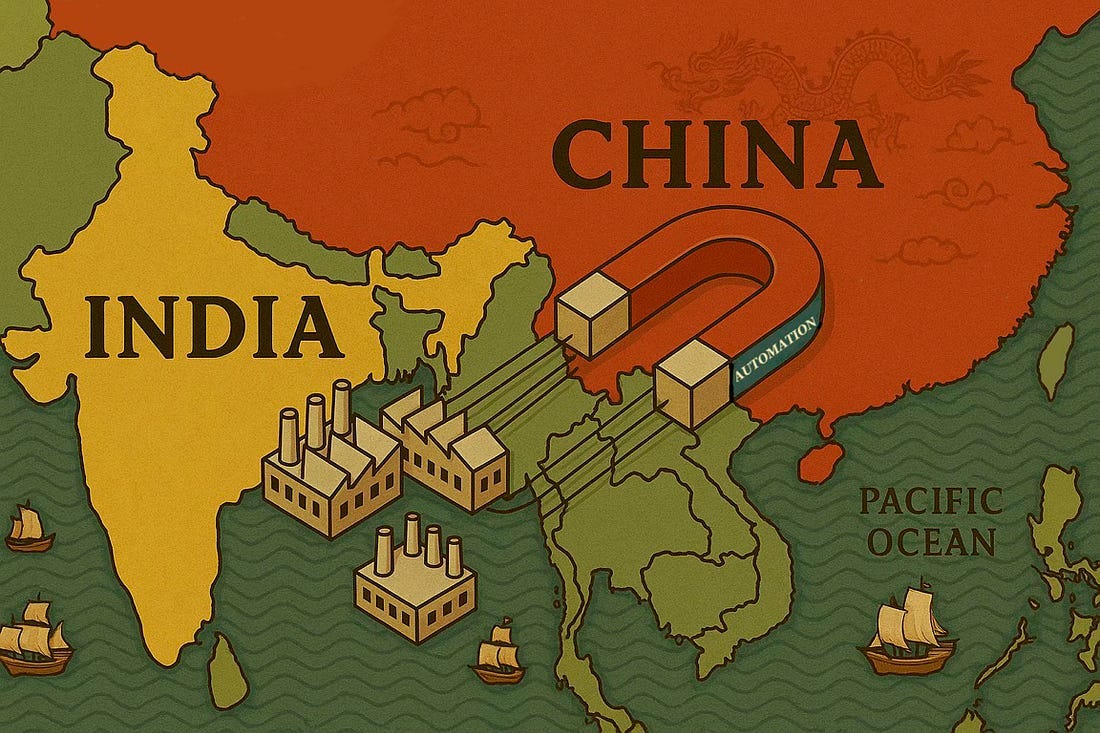

Professor Di aims to challenge conventional theories of industrial relocation, which describe the process of manufacturing migrating to less economically developed countries as production costs rise. In his telling, it is not just labour costs, but power—particularly maritime and technological power—which has historically determined where the centre of global manufacturing lies. Hence, rather than this centre inevitably shifting to countries with lower labour costs, China’s progress in automation and AI may be able to arrest this process—ensuring China’s pre-eminence in manufacturing for the foreseeable future. Underlying this argument is a conviction that above all else, manufacturing is the foundation of national strength. Presented within a sweeping macro-historical narrative of the past six centuries of industrial relocation, his argument strikingly resembles a theory of “the end of history”—albeit with manufacturing-inflected Chinese characteristics.

Beyond the contest to remain the world’s manufacturing powerhouse, Professor Di further contends that China’s strength in the realm of content creation and social media algorithms—particularly via Tiktok—could allow China to position itself at the centre of global information flows and thereby shape the dominant values and ideology of the 21st century. However, the scenario he sketches mainly involves the apparently lucrative business of adapting popular Chinese short-video formats to familiar Western settings; whether or not such content can meaningfully convey distinctly Chinese values is not immediately clear. Moreover, his fellow Renmin University professor, Wang Wen, has previously highlighted obstacles to China achieving a level of dominance in global discourse flows comparable to its manufacturing might—namely, informational “protectionism” in the form of the Great Firewall (which Wang has suggested dismantling).

Professor Di makes a case for China’s “centre-left accelerationism” as an alternative to both Western liberalism and the “Dark Enlightenment” of the American tech-right. Yet while technology and pure heft may allow China to maintain its role as the world’s factory even as its population grows wealthier, becoming the legislator of global values could prove a far more delicate balancing act.

— James Farquharson

Key Points

Traditional explanations of industrial relocation predict that global manufacturing will eventually shift from China to countries with lower labour costs, such as Vietnam and India—a process that has already partly begun.

As the Chinese government seeks to raise living standards and strengthen environmental protections—while demographic challenges remain unspoken—China faces significant upward pressure on labour and production costs.

However, China’s advances in artificial intelligence and factory automation could offset these effects, enabling it to resist the “gravitational pull” of relocation to lower-cost labour markets .

Whether or not China can overturn previous patterns of industrial relocation is key to determining if its rise to global prominence will be ephemeral or long-lasting.

This poses a more serious challenge than any threat of containment by the “American Empire”, whose power is already fading.

China may well achieve this. From a macro-historical perspective, the original industrial relocation from China to Europe during the 15th century stemmed from Europe’s superior maritime power—not lower labour costs.

If China can maintain its hold on global manufacturing through AI and automation, it would mark the long-term return of manufacturing to its natural centre of gravity.

Another crucial front in the development of artificial intelligence and online algorithms is the struggle to control the values, ideologies and narratives embedded in global information flows—a contest China must win.

The contest over global ideology and values involves three camps:

a)Left-wing neoliberalism – the declining ideology of the US’s Democratic Party;

b) Right-wing accelerationism – the elitist “Dark Enlightenment” thinking embraced by Silicon Valley and tech entrepreneurs aligned with Trump, currently on the rise;

c) Centre-left accelerationism – China’s “people-centred” techno-developmental ideology.

10. The algorithms underpinning Chinese social media platforms and artificial intelligence models will enable China to shape the values and ideologies of their users.

The Author

Name: Di Dongsheng (翟东升)

Year of birth: 1976 (age: 48/49)

Position: Deputy Dean and Professor, School of International Studies, Renmin University of China (RUC) (2017-now); Dean of the Institute of Regional and Country Studies, RUC; Deputy Director and Secretary-General, Centre for Foreign Strategy Research, RUC (2011-now)

Other: Frequent exchanges with officials at China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, International Liaison Department etc.

Research focus: Global political economy of money and finance; US political economy; Chinese foreign policy

Education: BA, MA and PhD Renmin University of China (1994-2004)

Experience abroad (as a visiting scholar or lecturer): Sciences Po Paris, Durham University, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Georgetown University