"China’s rapid expansion in the traditional chip sector has been a 'game-changer' since the outbreak of the tech war. If this expansion trend continues, China will gain strategic autonomy" – He Pengyu

Thomas des Garets Geddes, Kyle Chan, and Daniel Crain

Mar 19, 2025

DeepSeek gave the world a stunning demonstration of how China could work around US-led technology restrictions and find new paths for innovation. In a similar way, China’s auto industry was able to overcome challenges with internal combustion engine technology by innovating in electric vehicles and batteries. With semiconductors today, China is trying to get around technology restrictions using a host of strategies, including open-source RISC-V architecture, older DUV lithography, advanced 3D packaging and chiplets.

In this insightful commentary, He Pengyu (何鹏宇), a former student of renowned Chinese economist Lu Feng (路风), argues that China’s legacy semiconductor industry can play a special role in driving innovation. US restrictions on China’s semiconductor industry are aimed at limiting China’s progress on advanced semiconductors. Both US and Chinese policy efforts have tended to focus more on these leading-edge segments of the semiconductor industry rather than on so-called mature or legacy chips.

He Pengyu argues that this is a mistake. China should also prioritise the development of its legacy chip industry, which provides critical inputs for a wide range of sectors, including automotive, consumer electronics and high-tech manufacturing. China can leverage its position as the world’s largest chip market to drive scale and innovation in areas such as chip design and packaging

The history of Japan’s semiconductor industry offers a powerful lesson, He Pengyu explains. In the 1960s and 1970s, the US semiconductor industry was focused on what were leading-edge chips at the time for mainframe computers. Japan was able to leapfrog the US by pursuing a less-used technology called CMOS that offered greater power efficiency and was particularly suited for personal electronics like calculators, which Japan dominated. By the end of the 1980s, Japan controlled over 50% of the global semiconductor market, particularly through its production of CMOS-based DRAM.

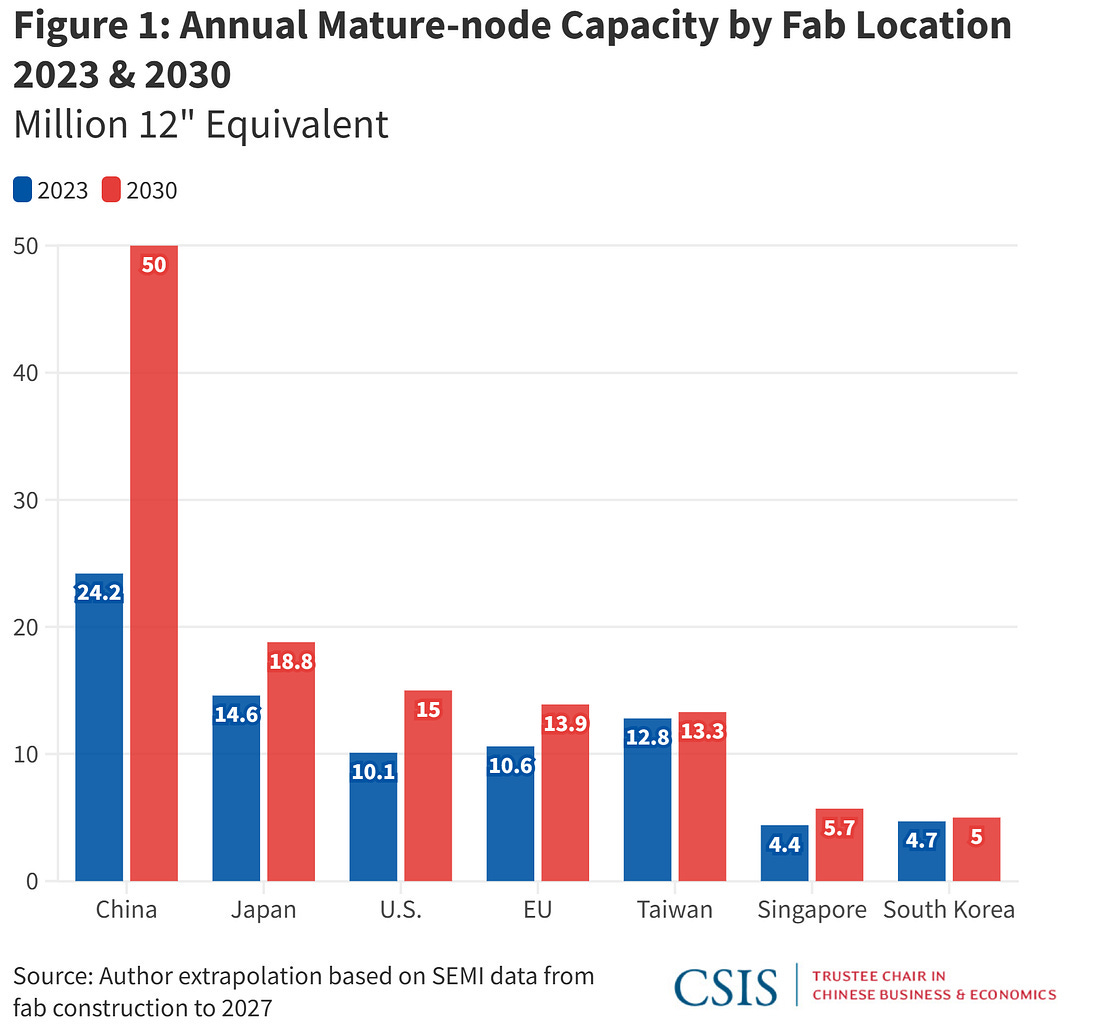

While leading-edge chips dominate the headlines, the US and China have both made efforts to address legacy semiconductors. China has been rapidly expanding its production capacity for legacy chips, which is expected to reach 39% of global capacity by 2027. Chinese chipmakers have already driven down prices for silicon carbide (SiC) chips, which are used for the power and automotive sectors. These trends have made the US and Europe increasingly concerned about possible Chinese overcapacity in legacy chips.

In response, the US is preparing to place tariffs on legacy chips from China, and the US CHIPS Act awarded funding to expand America’s own production of legacy chips. Going forward, He Pengyu argues, China may have the upper hand in legacy chips given its manufacturing dominance in many downstream industries, similar to the way that Japan used its calculator industry to catalyze its semiconductor revolution.

Source: Paul Triolo, CSIS

There are broader takeaways from this piece that extend beyond semiconductors. First, traditional industries should not be overlooked in the pursuit of emerging ones, a point made by Zheng Shanjie (郑栅洁), head of China’s National Development and Reform Commission. China’s industrial policy supports both, recognising that China’s traditional industries help enable its emerging ones.

Second, building up industries that are not necessarily cutting-edge but are large and diverse can provide a useful “training ground” (练兵场) to iterate and innovate. The scale and diversity of China’s legacy chip industry, for example, can drive progress in upstream areas such as chip design and manufacturing as well as downstream applications. Together, these various segments of the chip industry and their application sectors can improve together through a kind of “industrial coevolution”.

Third, innovation can happen along multiple dimensions. There’s a tendency these days to fixate on a single dimension of progress, such as the size of process nodes or scores on LLM benchmarks. But especially for companies or countries playing catch-up, there may be opportunities to leapfrog ahead by discovering entirely new axes of innovation. There’s a great expression that comes from racing: “overtaking on the curve” (弯道超车). When there’s a big shift in the industry, there can be opportunities for players that were previously behind to surge ahead.

– Kyle Chan

Key Points

America’s ‘Chip War’ against China, focusing on restricting access to advanced chips, left a strategic gap for China to rapidly expand its capacity in traditional 'mature-process' chips.

Most observers, both in China and abroad, have been seriously underestimating the economic and technological upside of expanding legacy chip-making capacity.

‘Traditional’ semiconductors account for over 70% of global chip consumption and hold pre-eminence in massive industries like automotive tech and consumer electronics. Dominating this vast market opens up huge revenue flows and opportunities for industrial upgrading.

Historical experience, notably Japan in the 1980s, shows that committing to scale in the chip industry enables latecomers to unlock innovation and productivity breakthroughs.

Although legacy chips may not rely on cutting-edge manufacturing processes, Chinese firms are driving innovation in chip design and advanced packaging, unlocking greater computing power without depending on the latest production technologies.

China should avoid the speculative, venture capital-driven ‘Silicon Valley model’ that prioritises funding mainly for cutting-edge chips with high profit margins.

Instead, China should favour a strategic approach that emphasises long-term output growth, cost advantages that attract foreign investment, and sustainable development—paving the way for industrial upgrading and market leadership.

In response to America’s attempt to apply a ‘chokehold [卡脖子]’ on China’s chip industry, China must not be afraid to implement reciprocal and assertive countermeasures against the U.S.

With self-sufficiency in legacy chip production now approaching, China is well-positioned to take such reciprocal action.

China’s biggest hurdle is no longer technology per se, but its entrenched inferiority complex vis-à-vis the developed West; confidence and strategic clarity will determine whether it surpasses global chip leaders. It is certainly on track to do so.

He Pengyu: “As long as China maintains political independence [独立自主], adheres to a “twin-track approach [两条腿走路]” in its industrial strategy—supporting domestic firms in building a competitive edge in traditional chips while persisting with the independent development of advanced semiconductors — then China’s technological catch-up and the overall rise of its semiconductor industry will be only a matter of time.”

First published in

IN THE MIDST OF THE U.S. PUBLIC OPINION WAR AGAINST CHINA, CHINA'S CHIP INDUSTRY MUST NOT FALL INTO THE TRAP OF “SELF-SABOTAGE” [自我阉割].

Dr. He Pengyu (何鹏宇) – Postdoctoral Researcher, School of Government, Peking University

Beijing Cultural Review (BCR) – January 2025

With special thanks to BCR and Zhou Anan for granting Sinification permission to share this article.

Translated by by Daniel Crain

(Illustration by OpenAI’s DALL·E)

READ the FULL TEXT in SINIFICATION substack